Anna Rabbit Malte Taffner, In a Garden State – Restart mag

Article in the Polish language.

Czy sztuka jest koniecznością, czy luksusem?

W świecie tonącym w plastiku i jednorazowych przedmiotach, czy możemy, jako artyści, usprawiedliwić tworzenie rzeczy, które przeżyją nas, a może nawet przetrwają nasz gatunek…

Getting Out (There), One Outfit at a Time

Sometimes dressing up is the only thing that gets me out of the house. It might sound silly, but it’s true. I’ve struggled with agoraphobia my whole life, and the pandemic made it infinitely worse. I never really bounced back from that. I don’t fully understand why it works, but putting on interesting clothes makes the outside world feel less hostile – as though I can slip into a version of myself brave enough to face it.

Agoraphobia – for anyone unfamiliar – is an anxiety disorder marked by an intense fear of places or situations where escape might feel difficult. For many, it means avoiding public spaces, crowds, or anything that requires leaving the house leaving the house. It’s a severe, often debilitating condition.

My style is uncontroversial enough that I only ever get compliments, yet bold enough that I do get compliments. That tiny social exchange, someone noticing the effort I put in, makes the world feel kinder. And I make an effort too. I always go out of my way to say something nice to older ladies who clearly put thought into their outfits. Young people intimidate me terribly, so I rarely bother them, but if they speak to me first, I’m perfectly happy to chat. Older women, though – they’re never in a hurry, and they’re always delighted to talk about clothes.

It’s much easier to leave the house if I spend 30–40 minutes carefully putting together an outfit and feel like I look amazing. I’m fully aware this is, in many ways, a temporary bandage. Yes, I probably need to work on the agoraphobia with a medical professional, but right now I have more urgent mental-health matters to sort out, and this is my functional workaround. It doesn’t cure anything, but it helps me live.

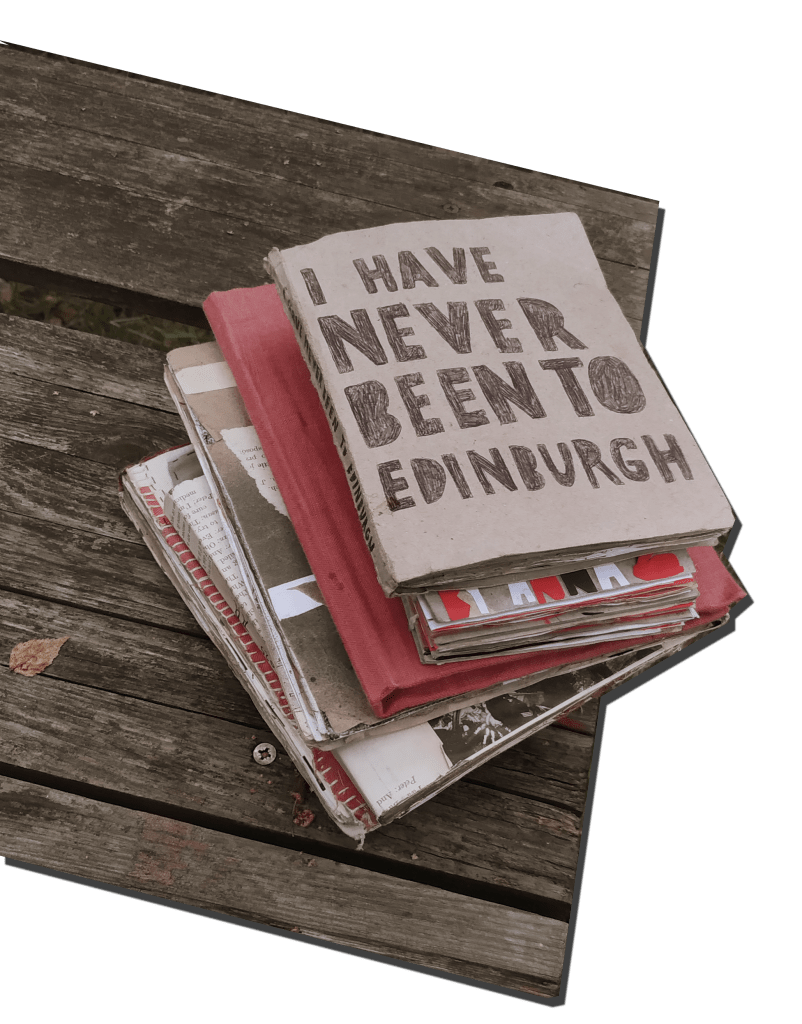

Another way I attempted to heal from my increasing fear of getting out of the house was pretend traveling. During the pandemic, when my fear of going outside was at its peak, I started a project called I Have Never Been To Edinburgh. I couldn’t leave the house, so I chose Edinburgh at random — a city I’d never visited, but found beautiful — and began making travel sketches by “walking” through it on Google Street View.

To this day, I still struggle deeply with leaving my house, especially when it involves travel. I haven’t left the country since 2020. And I still haven’t been to Edinburgh — the city I “visited” page by page when I couldn’t step outside my door.

I’ve gone off track — let’s go back to the clothes. Dressing up extravagantly is, frankly, my favourite form of armour. The more theatrical the outfit, the easier it becomes to step outside.

Sometimes the smallest rituals (dressing up, sketching distant streets) are what keep us moving, inch by inch, through a world that feels far too large.

P.S. I often share my outfits on Instagram, so take a look if you are interested in this kind of content:

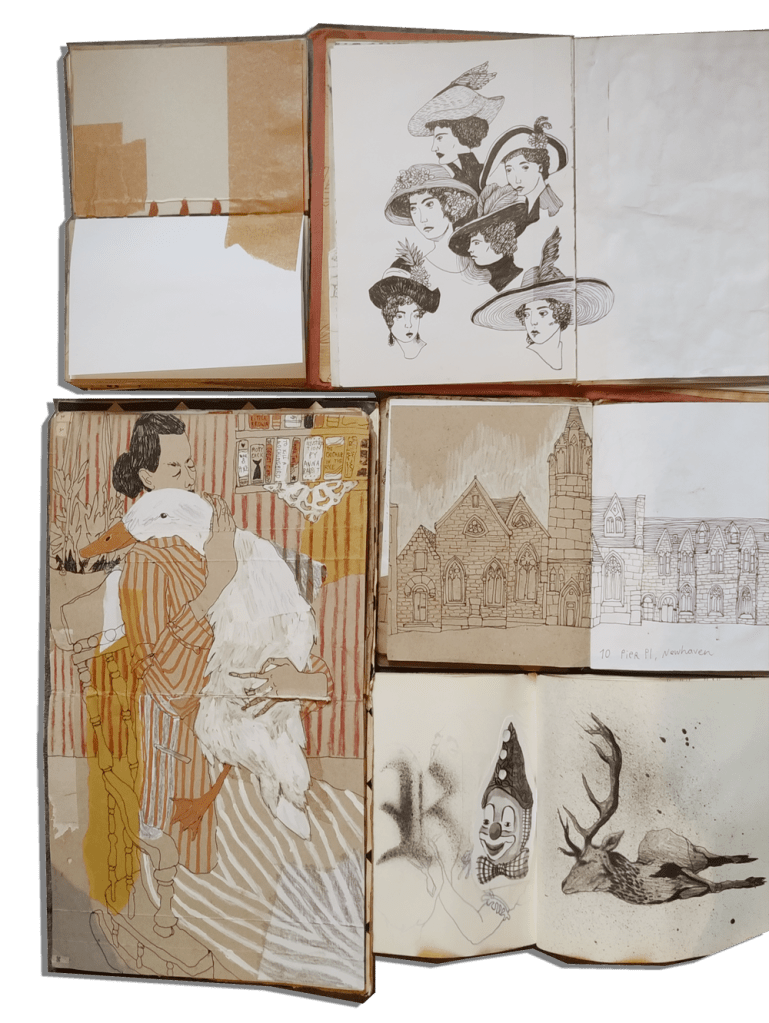

Sketchbooks as Independent Artworks

Introduction: Why Am I Obsessed with Sketchbooks?

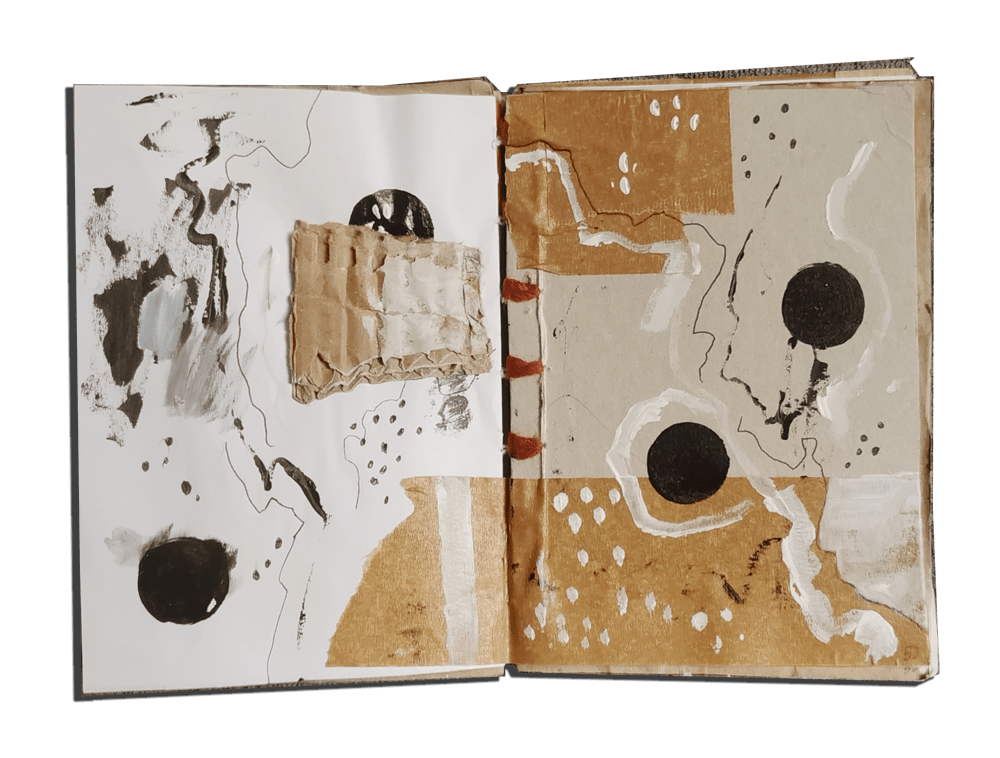

I have a personal agenda here, I’m not going to lie: I make sketchbooks. The fact is, I love them as an art form. I make them from scratch – I choose the paper (very often it’s recycled packaging paper), I bind, I smyth-sew them together. And then I draw in them. This way I can have different sizes and different kinds of paper. I can customize them to be exactly what I need at a particular moment.

During my years as a student at the Academy of Fine Arts in Kraków, I often saw sketchbooks exhibited among other art forms. But as a rule, they contain preparatory sketches for larger drawings or paintings. Rarely are sketchbooks presented as complete works – art forms in their own right.

The Edinburgh Project

My first serious experience with an art book as an independent art form, not a preparation for something, was my project I Have Never Been to Edinburgh.

I started this sketchbook during the pandemic and finished it only last year. At that time, I was struggling with agoraphobia and couldn’t leave the house. To cope, I invented a project: I picked Edinburgh at random (a city I had never visited, but knew was beautiful) and “travelled” through it using Google Street View, making sketches as if I were physically walking there.

I filled about 80% of the notebook during lockdown, then abandoned it until last year, when I showed it to a new friend who was from Edinburgh. When I started the project, I didn’t know him yet. He inspired me to finish the project. At my new friend’s request, I added sketches of his childhood street, his high school, and other personal landmarks. It added a nice little collaborative flare to this project.

But it actually already had another collaborative aspect from the beginning: all the dried plants in that sketchbook came from my long term Edinburgh pen pal (someone I met on Instagram, but never in person). She collected them, sent them in letters, and I glued them onto pages alongside drawings of the places where they were found.

To this day, I still struggle with leaving the house, especially when it comes to travelling. I haven’t left Poland since 2020. And I still haven’t been to Edinburgh.

The Lublin Mini Project

Let’s talk about I Have Never Been To Lublin as well, while we are at it. This is another of my “travel” sketchbooks, a short one, only 13 pages, all dedicated to Jewish heritage buildings in Lublin, Poland.

It’s a continuation (sort of) of the Edinburgh project, the same idea really. Except I actually have been to Lublin once – when I was fifteen years old. In fact Lublin was the very first Polish city I ever visited back when I wasn’t living in Poland yet. And now I have visited it once more (after the Lublin sketchbook was done) for the exhibition opening of my solo show based on these artworks.

This new sketchbook on Lublin is a bit different: it’s rooted in place and history, but it still carries that sense of traveling through drawing. Every page is focused on the Jewish heritage of the city, a way for me to explore and reinterpret its cultural memory through illustration.

The sketchbook is now part of the collection of Fundacja Żydowski Lublin and was first presented during the opening event of the project Mój Lublin. The program combines past and present, encouraging people to rediscover Lubartowska street and its rich cultural heritage. The evening featured music by Yuri Vedenyapin and an exhibition of my illustrations, shown as part of this broader dialogue between memory, history, and contemporary artistic practice.

Early Turning Point: Interdisciplinary Lab with Professor Bajek

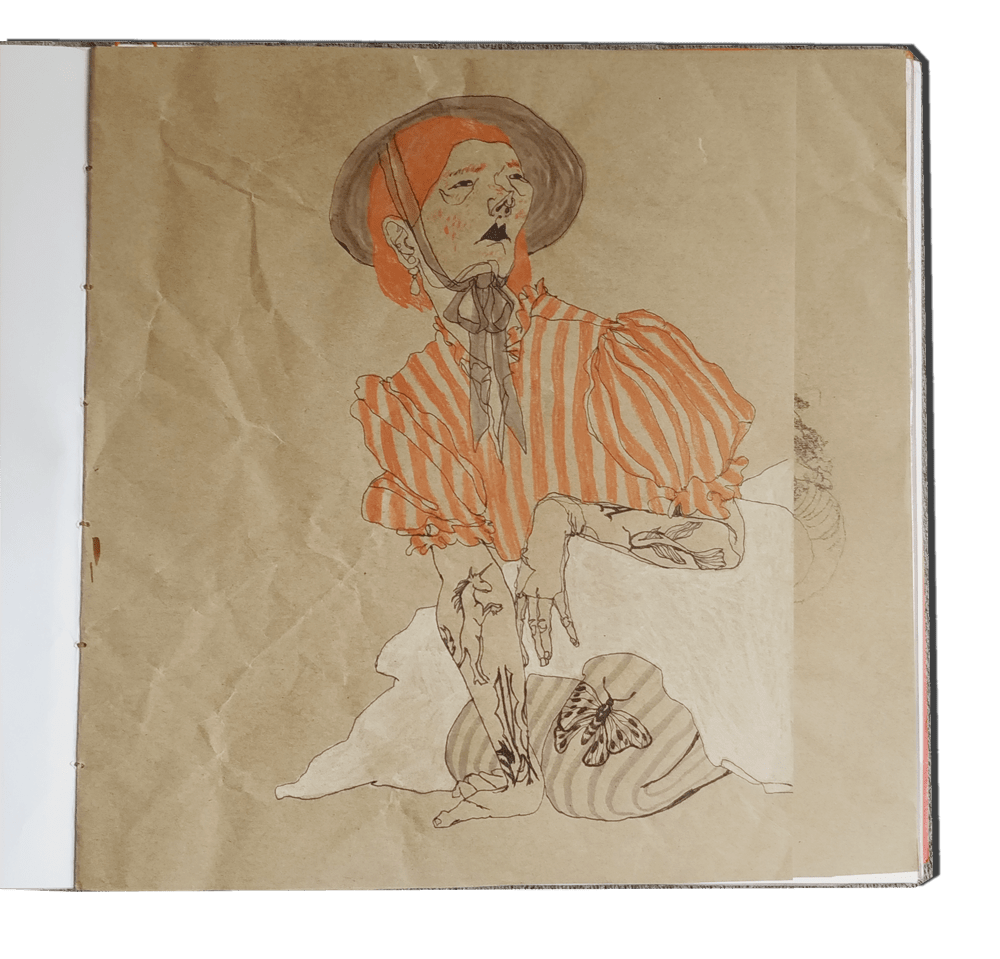

Another moment that convinced me of the independence of sketchbooks as art was the art book I created for my first-year interdisciplinary class with Professor Bajek.

The assignment was straightforward: a sketchbook meant to serve as research for my final project (costume design). But in the end, I liked the sketchbook more than the finished project. It was large and thick, very eclectic in style, had collages, drawings, sketches. It was a beautiful book (I don’t have it anymore as it is in the possession of Professor Bajek and he promised to intimidate all the future post graduate degree students with it). In fact the book was objectively better than my final costumes – partly because at the time I couldn’t photograph costumes properly, but still. The art book had its own strength, its own presence.

Exhibiting Sketchbooks: The Dilemma

Since those early projects, I’ve made numerous sketchbooks and art books, and every time I exhibit them I face the same dilemma: how should they be shown?

Do I let people touch them, flip the pages, interact with them physically – while risking damage or theft (which happened once in fact already)? Do I put them under glass, fixed on one spread? Do I film myself flipping through them and present that video, even though it robs viewers of the tactile experience?

I’ve tried all three approaches, sometimes because the gallery decided for me. I still don’t know which method I prefer. But I am determined to create and exhibit sketchbooks and art books for as long as I live.

Sketchbooks in Museums

It’s not just I who sees sketchbooks as more than research. A lot of famous artists had sketchbooks that are now exhibited in museums, and people actually line up to see them. For example, Frida Kahlo’s sketchbooks are in the Museo Frida Kahlo in Mexico City. They’re full of little drawings, diary entries, even personal confessions, and the museum doesn’t treat them as “drafts” but as part of her body of work.

Paul Klee’s sketchbooks are preserved in the Zentrum Paul Klee in Bern. What’s interesting is that they almost look like textbooks – systematic experiments with color and form, which later became the basis for his teaching at the Bauhaus. It’s basically a record of an artist thinking on paper. Needless to say this one hits very close to home for me!

There’s also Jean-Michel Basquiat’s sketchbooks, which MoMA and the Brooklyn Museum have shown. They’re messy, crowded with words and images, very raw. But again, they weren’t exhibited as preparation for something else – they were shown as artworks in themselves.

Even Picasso’s sketchbooks are kept and sometimes displayed at the Musée Picasso in Paris. Some of them are really just pages of doodles or compositional studies, but when you see them in person, you realise they hold the same weight as his finished paintings – they’re part of his thinking, but also complete little worlds.

Museums usually don’t apologise for showing this “unfinished work.” They frame sketchbooks as a way to get closer to the artist’s mind, but also as self-contained objects worth looking at. It makes me feel completely entitled to present my own books this way.

Other Artist’s Art Books

But let me briefly bring you back to Poland and to modern days, the year 2025 to be precise. This year I saw an exhibition that really stayed with me: Zu Ziny by Agata Jabłońska at the Kraków Comics Museum. Her art books fascinated me. They were made from her old school and university notebooks, full of notes, personal writing, drawings and even “sensitive data.” Instead of throwing them away or destroying them, she systematically painted over the pages in black – sometimes completely, sometimes leaving fragments visible so they turned into unique codices, poetry essentially. On top of this she added bold drawings, transforming something private and forgotten into something new.

It’s a completely different approach from mine – I never kept diaries – but one I admired a lot. What I found moving was the way she turned the so-called “sentimental trash” of her past into books that were whole artworks – another great example of art books that are not a preparation work for anything. It made me think again about how powerful the book format can be, how it can hold memory, erasure, and reinvention all at once.

The Love of Books (My Villain Origin Story)

Behind my obsession with creating sketchbooks stands my love for books. I’ve always been a reader. My favourite books are old repaired volumes, the kind with torn spines, dedications on the first page from 1972, notes and underlinings from readers I’ll never meet. I hate the polished perfection of freshly printed books.

Once, I read a copy that belonged to a close friend, filled with his underlinings. Reading it was a double experience – of the text itself, and of his perspective marked within it.

My passion for used books and book repair slowly shifted into book-making – first and foremost sketchbooks, as I was born a visual artist.

Time and Narrative in Sketchbooks

I like how versatile the format is. A sketchbook can be a collection of drawings, but it can also tell a story. Unlike most visual art, a book introduces time and sequence – narrative continuity.

I usually fill sketchbooks over months, sometimes years, since I work in several sizes at once and use them according to my needs. Any sketchbook with images is, in a way, a picture book or a comic. Even if it lacks a linear story, it still documents my growth as an artist, my shifting ideas, my experiments.

There’s nothing wrong with sketchbooks as preparation for other works. But I quickly learned they can be much more than that.

Case Studies: Sketchbooks in My Diploma Work

My diploma work “Cross-breed” (“Krzyżówka”) at the Academy of Fine Arts in Kraków contains quite a few books among other things so I wanted to talk about those as well.

The Book of Colour Combinations

This tiny book (10,5×15 cm) contains a series of abstract micro-collages. Some are pure collage, others include paint, ink, or crayon. Each was created with something in mind – sometimes a painting I was planning, art of another person, sometimes even an outfit.

Before you judge me for bringing fashion into this, I’ll remind you: costume and textile work are legitimate art forms, historically dismissed because they were coded as “female” crafts. Personally, I don’t think painting is superior to textile art or even to simply putting outfits together (aka styling), which for me is an art form (if it isn’t for you, you are doing it wrong). I’ll die on this hill.

Some collages made for outfits later became inspiration for paintings, and vice versa.

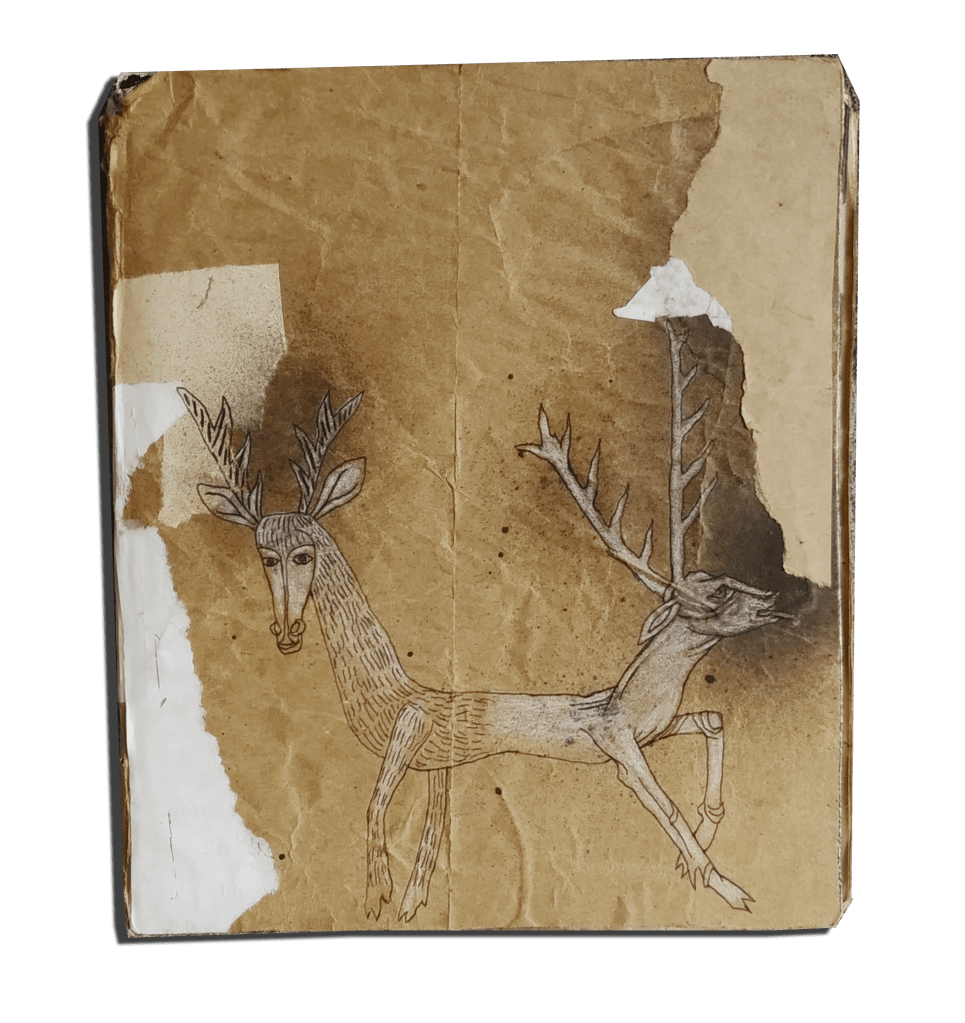

The Creature Book

This book (18,5×21,5) features a strange creature on the cover, based on a tattoo on my upper back (itself inspired by an 18th-century engraving). Inside are illustrations exploring human-animal relationships.

Most of these drawings never became larger works, which is why I see the book as a finished artwork in its own right rather than a preparatory sketchbook. It also helps that most pages are fully realized illustrations, not sketches.

The Traditional Sketchbook

This one (35×35 cm) is closer to the conventional form: a sketchbook filled with preparatory sketches for the paintings included in this diploma project.

Conclusion

Looking back at all these projects, I realise that sketchbooks are the backbone of my practice – not because they prepare me for “real” artworks, but because they are the real artworks. They embody something few other formats allow: intimacy, portability, and a living sense of time. A sketchbook is never a single frozen moment like a painting on a wall – it unfolds, page by page, with rhythms, pauses, and juxtapositions that belong only to the book form.

For me, making sketchbooks has also meant reclaiming the authority to decide what counts as finished. In art school, I often felt pressured to prove myself through large-scale paintings, installations, or performances, as if smaller or more private works could never hold equal weight. Yet my strongest pieces have often been these books. They hold not only images, but memory, doubt, failure, and play.

Most importantly they hold the change I undergo.

They carry the traces of friendship and collaboration, even the imprint of places I’ve never actually visited. In that sense, they are not only artworks but also maps of my own lived experience.

When I see sketchbooks by Kahlo, Klee, or Basquiat preserved in museums, I feel that I am not straying off course by calling my own sketchbooks artworks. If anything, I am joining a long tradition of artists who refused to draw a hard line between the “preparatory” and the “complete.”

So if I keep making these books – and I know I will – it’s not just because I love the craft of binding and the tactile joy of turning their pages. It’s because sketchbooks allow me to tell stories that cannot be told on a canvas. They are complete, imperfect, and alive.

This text was written by Anna Rabbit in the year 2025 – parts of it were included in a written part of Anna’s diploma work “Cross-Bread” at the Academy of Fine Arts in Kraków.